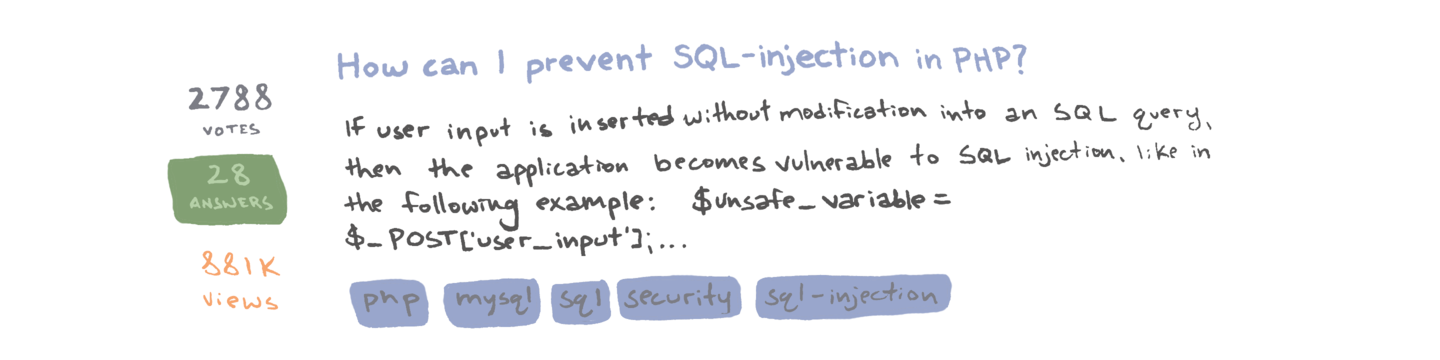

hen you search online for an answer to any programming question, chances are the first page that will show up will be Stack Overflow. Founded in 2008, Stack Overflow (Stack, for short) is the world’s largest question-and-answer site for all things computer programming. Used by over 40 million people a month, it has become an indispensable tool for nearly every computer programmer in the world. In a focus group conducted by Stack in cities ranging from Berlin to Tokyo, one programmer likened Stack Overflow to the oxygen in his lungs. Without it, he simply could not do his work, or for that matter, live. Others laugh when asked about its importance, saying that if the site went down for even a minute, you would have a global riot of programmers on your hands. Alongside Stack Overflow, the Stack Exchange network hosts another 153 question-and-answer sites that cover topics ranging from astronomy to home improvement, which all told reach an additional 60 million users per month.

Stack Overflow is not just a unique company in that it has become an essential tool for programmers in a world increasingly dominated by software, but because of its co-founder and CEO, Joel Spolsky. For years, Spolsky has been one of the foremost voices in the world of software development, largely due to his books and influential blog, Joel on Software. Spolsky has written extensively on the best hiring practices for developers and how to create a productive workplace. His decisions often have gone against the grain of contemporary Silicon Valley culture, such as his choice to give all programmers private offices and make remote work a fundamental pillar of his companies (over one-third of employees at Stack Overflow work remotely). Spolsky’s companies have met considerable success, and along with Stack Overflow, he helped found Trello, a project management tool that has over 5 million users.

Spolsky’s vision for the modern workplace is clear at the Stack Overflow headquarters, which takes up two and a half stories of an office building in the heart of Manhattan’s Financial District. An open cafeteria serving gourmet lunches every day meshes with a café, replete with a La Marzocco espresso machine and the light sounds of the David Bowie Pandora station playing over loudspeakers. The office managers at the front desk juggle, order an unceasing supply of drinks and snacks, and dole out high fives to co-workers passing by. Stack Overflow has become known for its office culture, and in 2015, it was voted the 4th best place to work in New York by Crain’s. There is an atmosphere of care and passion at Stack that runs through every action. Employees describe this place as their second home, and their co-workers as family, and they mean it. Joel Spolsky has not only created a website that is helping most of the world’s software get made, but also a workplace where employees feel an incredible sense of community amongst their co-workers, and passion for their jobs. This passion, however, hides a larger story of the way companies like Stack Overflow are branding work as play to create increasingly productive workers.

t’s a typical afternoon at Stack Overflow and the ad sales team is busy at work on the 26th floor. Joseph Lippens, a senior account executive, sits typing away at his computer. He’s a slightly burly guy, dressed in jeans and a t-shirt, with a faded tattoo peeking out on his right bicep. He steals a glance behind him and quietly reaches for his gun. It’s a standard issue Nerf N-Elite Triad EX-3 Blaster. Jarrod Weaver, a senior account exec with thick-rimmed glasses and a healthy goatee, is focused intently on his screen. The coast is clear.

Joseph steadies his hand and fires, letting out a resounding pop. The orange-tipped projectile whizzes through the air and bounces off Jarrod's stomach, joining a litter of other bullets on the floor. On cue, Danny Miller, the director of the ad sales team, grabs his gargantuan Nerf Hail-Fire Blaster, and shoots Will, an ad campaign manager, in the head. Things begin to escalate.

Steve Feldman, an ad operations manager and the amiable prankster of the group, jumps from his desk, grabs his gun, and dives into a big cardboard box filled with packing peanuts. From his hideout he begins to rapid fire Nerf projectiles, as the whole ad sales teams kicks into action. Joseph ducks behind a column in the middle of the room, peeking out to fire back at Steve, while others run for cover and grasp for more ammo on the floor. After ten minutes or so of intense volleying, the team resumes their positions and gets back to managing accounts.

Although big battles like this don’t happen more than once a month, Nerf guns play a prominent role on the ad sales floor at Stack Overflow. Over lunch one day in late February, at the Stack offices, Joseph Lippens described how “potshots,” one-time shots, happen every day – usually between him and Jarrod, who sits diagonally to him. The larger battles happen less frequently, but when they do, the ad sales team takes them seriously, especially Steve. Steve often jumps onto a furniture dolly, and scoots along the floor on his back shooting his Nerf gun, as if in an action movie. As he puts it, “when we start fooling around like kids, I want to act like a kid."

The Nerf wars are just one element of joking and play that occur at Stack Overflow. Steve also described the office’s love for pranks. He recounted how one time he and few co-workers ordered 75 plastic playpen balls and then proceeded to launch a full-on attack on the office manager Adam, concluding with dumping a large quantity of the multicolored balls onto his desk. Other pranks of recent memory include individually wrapping every object on a co-worker’s desk and Steve returning from holiday to find dozens of coffee mugs emblazoned with his face, seemingly multiplying around the office.

While someone outside the office might view these jokes as annoying, if not malicious, Steve describes them as a way of building trust. For him, pranks are a way of showing you care about your fellow employees, and that they “trust you enough to not be angry.” He says this trust plays a crucial role in the business side of the work and creates an environment where he can feel comfortable telling a co-worker they “fucked up” this or that ad campaign, and know they won’t take it personally. At Stack Overflow, Steve says, pranking and play Nerf gun battles are a way of showing you care about your fellow co-workers, creating team harmony, and being a successful company.

Joseph Lippens, the instigator of many of these Nerf wars, seems to agree:

n 1996, the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), an international economic organization consisting of over 30 high-income countries, published a report titled, “The Knowledge-Based Economy”. Amidst the growing proliferation of dot-com and software companies, the report sought to define a transformation in the global economy. What the report outlined was the knowledge economy, the successor to the agricultural economies and industrial economies that had dominated before it. According to the OECD report, knowledge economies, economies “directly based on the production, distribution, and use of knowledge and information,” were increasingly becoming the drivers of the world’s most developed countries.

It is important to note that these different economies do not fit neatly, one after the other, on a timeline, but instead co-exist and overlap. For example, agriculture in the United States uses both industrial machinery to gather crops on a massive scale, as well as knowledge-based technology to optimize harvests. If the idea of the knowledge economy is confusing, it is because the definition is broad, and shared by a wide range of companies that produce everything from Internet search engines to cures for vision loss. For example, biotechnology companies may make their money off physical drugs, but their business is the business of ideas and knowledge. In order to make money, they are constantly trying to figure out answers to how different biological systems in the body work, in order to create drugs that can target those systems when they fail. Whereas an industrial manufacturer of the 20th century like Ford would have been more focused on making its production process more efficient, and churning out the same, if not similar, product, knowledge-based companies pour significantly more resources into coming up with new ideas. It is not that innovation wasn’t present or necessary in a manufacturing company like Ford, but in modern knowledge-based companies, the speed of innovation has increased many-fold. Biotech companies will work on hundreds of drugs at the same time, in the hopes that one will succeed and cover the cost of all the ones that weren’t profitable. The pressure to come up with so many new products, at such a fast pace, simply was not present for the manufacturing companies of the 20th century.

In addition to this, the technological and business landscape is shifting more rapidly than ever before, meaning a product that was successful a year ago, may be redundant today. A famed example is Microsoft, which for many years was the industry leader in personal computers. In the late 2000s smartphones began to catch hold, and by 2013, shipments of PCs were declining at a rate of 9.1%, according to the International Data Corporation (IDC). Microsoft scrambled to enter the smartphone market but could not catch up to competitors like Apple who had spearheaded the new technology. Microsoft’s story shows how in the knowledge economy, where products can quickly become irrelevant, keeping ahead of the curve through constant innovation is a necessity for success.

Innovation is a hard word to define, because at its core, it is about changing definitions, transforming what was perceived to be the norm. The Oxford English Dictionary defines innovation as “the alteration of what is established by the introduction of new elements or forms,” but also as “the action of introducing a new product into the market.” Innovation is about newness, generating ideas and products that did not exist before. The word has become a buzzword in everything from Obama's State of the Union addresses to car company branding, and since 1950, its usage in books has gone up by 150%, according to Google Books. It is not mere coincidence that the rise of the knowledge economy and America’s obsession with innovation have come hand in hand.

Knowledge-based companies are fast becoming the largest source of capital in developed economies. According to the OECD, in 2005, high tech manufacturing exports in America already made up 35% of all manufacturing exports, and that was just for the tech industry. Along with tech companies, knowledge-based companies include the likes of biotech firms, consultancy groups, and advertising agencies. Luis Suarez-Villa, a professor of social ecology at UC Irvine has written extensively on the knowledge economy and its need for continuous innovation. For Suarez-Villa, the knowledge economy is part of a new phase of capitalism, which he terms technocapitalism, where companies mainly deal in intangibles such as creativity and knowledge. For these companies, the constant creation of ideas is a prerequisite to viable business. On his website dedicated to the subject, Suarez-Villa writes:

Suarez-Villa shows the great uncertainty surrounding knowledge-based companies and the pressure on them to create new ideas that will be profitable. Companies like Alphabet (Google’s parent company) pour massive investments into research and development, not knowing whether these investments will pay off. In order to offset the possible failure of one venture, knowledge-based companies have to systematically come up with innovative ideas. This need for systematic innovation has led to the transformation of the workplace, as knowledge-based companies try to create environments where innovation is the norm.

Stack Overflow in many ways epitomizes the knowledge economy. It is a company that allows tens of millions of programmers to produce and share knowledge, by posting and answering programming-related questions. Its own programmers (who almost always use Stack Overflow to build the site itself) then help make the site an easier and better place to share this knowledge. On top of this, Stack makes its money from selling knowledge. It connects employers to programmers through job placement ads, and gives employers information about what skill sets programmers have in order to find the best fit for their company. Beyond this, Stack Overflow drives innovation across the entire knowledge economy. Internal company studies have shown that every programmer in the world has either heard of or used Stack Overflow to solve a problem. Tech giants like Google and Facebook have forgone many of their internal tech forums, and primarily use Stack to solve programming questions. As a whole, Stack helps companies across the knowledge industry produce code (and ideas) better, and save time doing it.

Stack Overflow was founded on the belief that a fantastic place to work will produce a successful company in our modern economy. In the late 90s, its co-founder Joel Spolsky, was fed up with the lack of good employment opportunities for programmers. As a veteran programmer himself, Spolsky felt that most companies did not understand programmers, and treated them like cattle, shoving them onto a packed floor to churn out code day and night. He and a partner, Michael Pryor, founded Fog Creek Software in 2000 as a great place to work for programmers. According to the Vice President of Community at Stack, Jay Hanlon, Spolsky and Pryor wanted to create a company where people would “love what they do.” Programmers all got their own offices, a common lunch was served every day, and everyone’s opinion mattered in steering the company toward its next venture. Spolsky’s belief was that good ideas would follow, and they did.

Fog Creek produced a wide-range of tools that became widely influential among programmers, the first being FogBugz, which helps keep track of bugs and issues in computer programs. By 2008, Fog Creek launched Stack Overflow, followed by Trello, a project management tool, in 2011. What Spolsky and his partners realized, was that in order for the modern tech company to thrive and continuously innovate, it needed to change the workplace.

A year before Spolsky founded Fog Creek, in 1999, the movie Office Space came out. It told the story of a disgruntled employee, Peter Gibbons, who worked at a fictional software company called Initech. Despite being in the business of making software, Initech was deeply steeped in traditional corporate structure. Cubicles divided the entire office, there was a set corporate ladder, and employees along the chain of command felt little passion, purpose, or ownership in the work they were doing.

The workplace in Office Space was representative of a larger corporate structure that entrepreneurs like Spolsky were actively seeking to reject. Whereas in the traditional corporate world companies distributed amenities hierarchically, the CEO getting the private plane and the accountant getting discounted parking, knowledge-based companies like Spolsky’s turn this inequity on its head.

In contrast, at Stack Overflow amenities are distributed equally across employees, everyone receiving gourmet lunches, monthly metro cards, video game rooms, and even office treadmills if they so please. At lunch, Spolsky sits with everyone, and within the sea of hoodies and t-shirts, peoples’ respective positions within the company are obscured. Even the hierarchy of positions is largely subverted, with departments being more spread out and collaborative than a top-down chain of command. In Spolsky’s vision, having employees happy to come to work and feeling like they are building something of value with their coworkers, is a prerequisite for an innovative company. The knowledge economy has promoted a push towards innovation in the workplace, that is not merely transforming the way people work, but changing the very idea of work in the 21st century.

By encouraging employees to contribute original ideas to the company through hands-off management styles and designing the office space to foster creativity, companies like Stack Overflow are promoting the idea of work as a self-fulfilling and purpose-driven endeavor. The worker is painted as a crucial stakeholder in the company’s future and thus work increasingly becomes about self-direction and passion, as opposed to mindless, menial labor. Even when the labor at Stack Overflow is mindless and menial, it is still roped into this rhetoric of passion and purpose. Stack’s Vice President of Operations Alex Miller, describes how the office managers, who keep the office clean and order snacks among other things, play a crucial role in the success of the entire company. He says the office managers “aren’t just stocking a lunchroom with food. They’re creating an attitude and a feeling that is going to infuse out to everyone else, that is going to affect how good those people are at their job.” In the effort to squeeze the maximum amount of creativity and innovation out of workers, knowledge-based companies are instilling even the ordering of snacks with a sense of purpose.

On top of this, the modern workplace bent on innovation obscures markers of class and status, in order to place further emphasis on the importance of original ideas. At a company like Stack, an employee’s original ideas and contribution matter much more than their job title. By encouraging people to take off the suit and tie, and distributing amenities equally among employees, traditional markers of status and hierarchy are beginning to disappear. The fact that the Chief Financial Officer at Stack plays beer pong on the same team as a mobile developer at Friday night beer bashes speaks to a new measure of status that is emerging out of startups. Employees are not valued by the clothes, cars, or job titles they own, but by their contribution to the innovation of the company.

This mentality is seeping into mainstream American culture as a generation of millennials is finding a sense of identity, less in luxury items than in their entrepreneurial drive and desire to innovate, whether it be a company that sells water in milk carton boxes or a matcha tea bar. Indeed, the slogan for Boxed Water reads: “Reach for Better. Pure water with a purpose.” Increasingly everything, including water in boxes, is being tied to a larger rhetoric of purpose and progress. It is not that the turn towards meaningful labor and creativity is new, one only needs to think of the counterculture movements of the 60s and 70s. But what is new, is the unceasing rhetoric of innovation that in many ways has replaced traditional markers of class. One’s social capital today, at least in the urban metropolises of America, seems to be more and more tied to his or her entrepreneurial zeal and potential to innovate, and less to material wealth. While the push towards innovation that the knowledge economy has given birth to is having far-reaching implications, its contours are being actively shaped at companies like Stack Overflow. In order to understand the way the modern idea of work is being transformed and the consequences it’s having, it is necessary to step further into the modern office.

veryone looks forward to lunch at Stack Overflow. Like clockwork, every day a few minutes before noon, the New York office’s 100-some employees pour into the 28th floor common space. The two full-time chefs, Phil and Shanna, mill around adding last-minute platters to an already full buffet as employees line up with plates. The menu, scrawled on a white board at the beginning of the buffet, is usually impressive, and filled with farm-to-table standards like kale and avocado that have become synonymous with the urban, creative, upper-middle class. The chefs pride themselves on the fact that every day they create a new menu, and have gone through so many different ethnic cuisines that they have started to combine them. On one such occasion, the chefs themed an entire meal around gourmet meatballs, with meatballs hailing from Sweden, Ethiopia, and Morocco.

After getting food, employees sit down at long common tables and eat. There’s a sense of civility and leisure as people take their time, helping themselves to seconds and dessert, and often idle around, talking to co-workers for over an hour. People usually sit at the same tables everyday, and each table more or less corresponds to a different team in the company. The career sales team (people in charge of selling job placement ads on the site) sits together at the last table, and the closest table to their sales floor.

Repeatedly, employees at Stack discussed how the career sales team is on a different wavelength than the rest of the company, and prefer to get back to their desks to make sales calls, instead of having a long, chatty lunch. They work on commission, and the more time they are at lunch, the less time they have to make calls. Indeed, on most days, the career sales team is the first to push back their chairs and leave their plates in the common dishwasher.

On the table next to the career sales team sits the ad sales team which is responsible for selling banner ads on the site. These are the block ads on the top, bottom, and sides of the website.

The ad sales team is smaller (around 9 people, compared to a career sales team of almost 40) and tends to hang out at lunch for longer. Beyond their table, the groups become more diffuse with programmers, people from the community team (those in charge of making sure questions asked and answered on Stack websites meet quality standards, among other things), and the finance team, all sitting together. On the very last table, a group of 4 or 5, informally called “the crossword club” by some employees, sits and completes New York Times crossword puzzles every day. They are religious about this and come armed to the table with printouts of the day’s puzzle and their preferred writing utensils.

The common lunch at Stack is a way of building community and a sense of togetherness across the office. Employees talk about everything from office gossip to highly technical discussions on server frameworks. Instead of breaking off into smaller groups and rushing to get lunch outside, employees get more of a chance to connect and interact with each other. This creates an atmosphere that Stack’s CEO Joel Spolsky thinks is essential to a good workplace.

Spolsky has long been a proponent of common lunches. On his blog, Joel on Software, Spolsky writes:

What Spolsky does not mention is that this desire to create a “humane workplace” is not simply an act of goodwill to programmers around the world. It is undergirded by the belief that a “humane workplace,” one that makes people happy to come to work and encourages them to interact with their colleagues, will promote innovation, and ultimately profit.

While Spolsky may not overtly discuss the motivations of profit here, this is a belief that is discussed at the highest levels of leadership at Stack Overflow. Alex Miller, the Vice President of Operations at Stack, described how providing common lunches was in part driven by the idea of decision fatigue. As he explained it, decision fatigue is “the idea that as you make more and more decisions, your ability to make decisions goes down.”

Miller went on to say that “by providing lunch at noon every day we are doing two things: one, we’re creating a great bonding point for everyone.” Two, we are ensuring ”that people do actually eat. Because food is stressful for a lot of people, and by taking care of that we’re letting them just not have to think about it, not devote mental energy to it.”

Providing a common lunch at Stack Overflow is in part driven by the desire to increase employees’ productivity. It is another manifestation of the desire, and necessity, for knowledge-driven companies to create a workplace that is geared towards constant innovation. In a world where startups are fighting tooth and nail to come up with the next new idea, companies like Stack Overflow are doing everything they can to give their employees the upper hand. If an employee does not need to think about where they are going to get coffee, or what they are going to eat for lunch that day, they have more energy to solve problems at work, or come up with an innovative idea.

This idea of decision fatigue expands beyond the lunchroom. The CEO of Facebook, Mark Zuckerberg, cites the idea as his rationale for wearing the same outfit everyday. By not having to decide what to wear every morning, he is able to save decision making potential for problems at work.

Along with lunch, Joel Spolsky’s philosophy of pluralism is another way that Stack Overflow instills workers with a sense of purpose and encourages creative thinking. Pluralism is a management philosophy that Spolsky routinely cites as foundational to the company. Vice President of Community, Jay Hanlon, describes it as “trying to service leadership” and “empowering people to make more decisions,” as well as “have more autonomy.” This is achieved through reversing the management structure and making everyone feel like they can contribute meaningfully to the company’s future. Employees at Stack describe the management structure as a reverse pyramid, where developers and sales associates are at the top, and managers and executives are at the bottom.

By removing strict hierarchies and making managers more of a support role, Stack is trying to make employees feel more ownership over the company, and be more inclined to spur positive change. Joseph Lippens, an account executive on the ad sales team and a protagonist in the company’s Nerf wars, discussed how he and a few colleagues independently came up with the idea to create a homepage buyout for advertisers. This means showing every unique visitor to Stack Overflow’s homepage the same advertisement, the first time they access the page that day. The campaign was a success and the homepage buyouts reached over 3 million unique visitors every day. Describing the experience, Joseph said, “we created this idea just sitting around one day, we cleared it through a couple of our meta pages and a week later it was rolled out. It didn’t take teams of people to approve and lawyers to look at it. We just said ‘no, we can do this’ and it was done.” By removing bureaucratic ladders and encouraging the creation of original ideas from any corner of the company, employees like Joseph feel motivated to go beyond the routine obligations of work, and help Stack Overflow innovate.

While employees at Stack don’t use the word “innovation” all that often, it is the subtext for the work they do. There is an absolute focus on solving problems, solving them creatively, and finding new ways to expand the scope of the company. This spring, Stack was preparing to launch a new feature called Documentation which will be a definitive resource and encyclopedia for programming languages, whose user guides often times are very hard to navigate. It is new products like this that exemplify the innovation Stack is trying to drive, and the reason the company has promoted common lunches and the philosophy of pluralism. Through making employees feel part of something larger, and that they are passionate about their work, Stack is helping cultivate incredibly productive laborers – laborers made for innovation, laborers made for the knowledge economy.

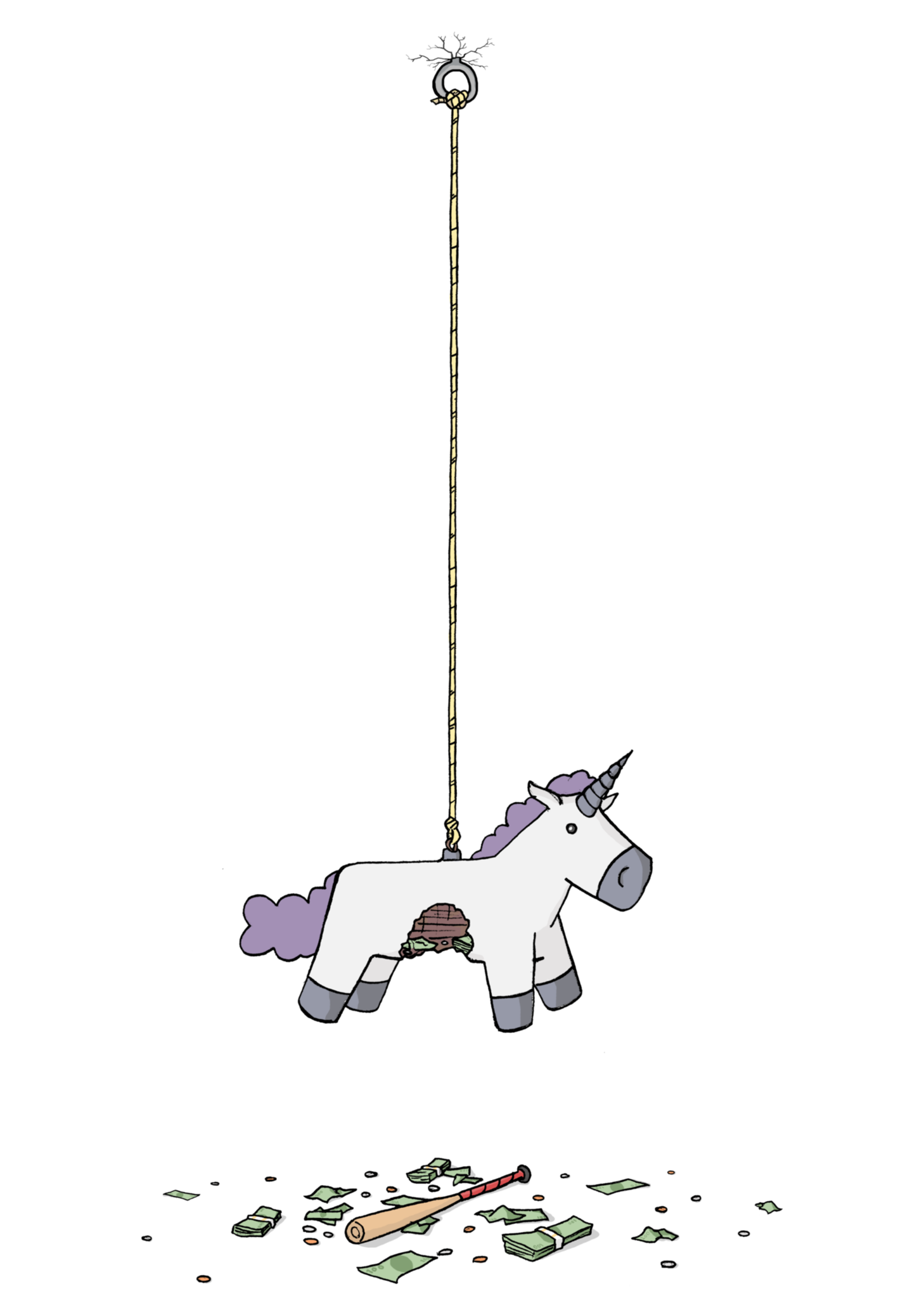

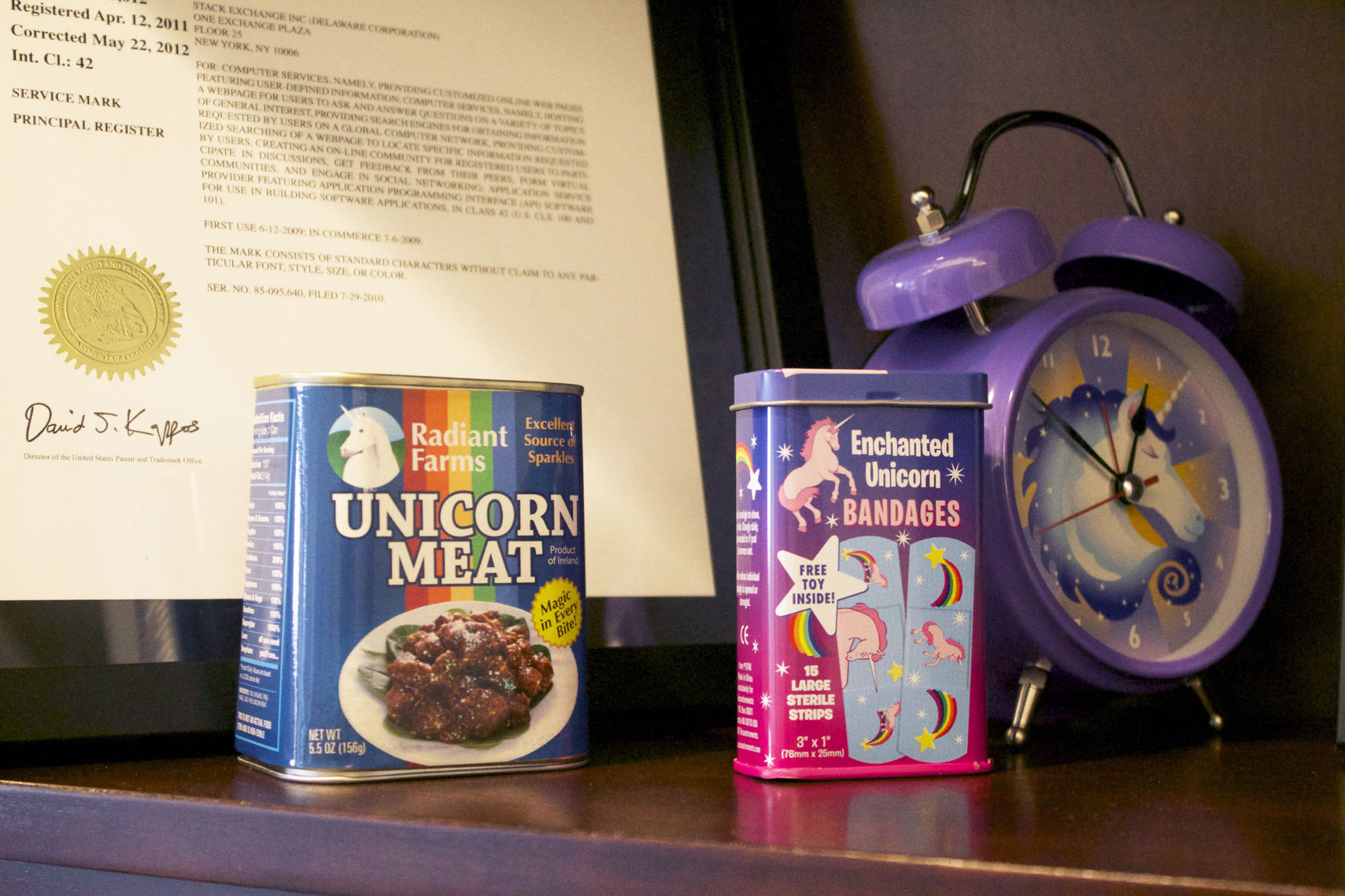

here are unicorns everywhere at Stack Overflow. They’re perched atop desks in stuffed animal form, they’re drawn on walls, and they’re in unicorn clocks. There are even cans of “Enchanted Unicorn Bandages” and “Radiant Farms Unicorn Meat” that line a shelf on the company’s wall of fame.

Stack loves unicorns, and according to multiple employees, they have become an unofficial mascot of the company. Within the tech world, unicorns have come to mean a startup that reaches a one billion dollar valuation. The term has gained mythic proportions just like the creature named after it, and symbolizes an aspiration for entrepreneurs and programmers alike. But beyond its aspirational value, the unicorn also hides a shadier side of the tech world.

Companies disguise the pursuit of profit through playful and motivational images like the unicorn. You are not just working for dollars and cents, but for something greater, something in the realm of rainbows and mythical one-horned creatures. When the sock-eyed gaze of capitalism is replaced by the batting white eyelashes of a unicorn, work seems so much better than work. However, behind the batting eyelashes, within the Trojan unicorn, hides the reality of profit-driven labor. The word “innovation” works in the same way, papering over the fact that employees are working incredibly long hours to produce capital, and instead branding work as creative liberation. Just as the unicorn makes the pursuit of profit seem playful and fun, so does the word “innovation” rebrand work to make employees produce more, faster. In our latest stage of capitalism, the language of innovation is being used extract more creativity and labor from workers, while obscuring the role of money.

The thing is, it's not that bad. In fact, as tech companies go, Stack Overflow is among the best. Workers at Stack don't feel exploited or particularly overworked. They are compensated well, enjoy great benefits, and feel connected to the work they produce. The tech industry is not creating a dystopia, but it is making people forget that “innovation” in our day and age more and more just means plain old “production.” The workers of today and tomorrow should be wary of forgetting that within the purpose-driven, passionate, caring workplace, money is still the core of what is being produced. For creativity to truly bring about sustainable change in our latest phase of capitalism, it must be grounded in reality, and be aware of the system it is working for. So next time you see a unicorn, think twice.